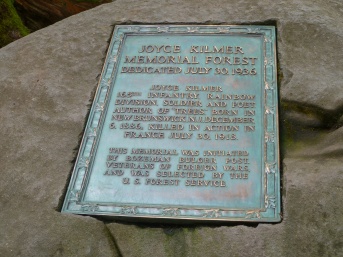

Given this blog’s homage to Joyce Kilmer, how could I not devote a post to the mighty trees of the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest? Born in New Jersey, Kilmer had no connection with North Carolina, but the 3,800-acre forest within the Nantahala National Forest was dedicated to him in 1936, as a memorial both to his poetry and to his service in World War I, where Kilmer paid the ultimate price for his patriotism.

My oldest son and youngest son, ready for adventure!

In the summer of 2012, accompanied by my husband and two of my sons, I made the two-hour drive from my house to visit those Appalachian giants. Alas, the June day was unseasonably warm, so the first part of our two-mile hike through the forest was less pleasant than anticipated–particularly after my oldest son was attacked by a stinging insect shortly after we started the figure-eight trail. (The cheerful photograph on the right was taken at the trailhead.)

Not only were the humidity and bugs an issue, but, on the lower portion of the loop, there was less shade than I would have expected in a famous forest. Later, I learned that in 2010 the United States Forest Service used dynamite to remove many dead hemlocks that had fallen victim to the invasive woolly adelgid and posed a safety hazard to visitors.

Eventually, we made our way through the blasted remnants of the dead hemlocks to the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Plaque, which was a good place to take a short break from hiking.

Now that we had entered the Poplar Cove section, I began to understand why this old-growth forest was worth a two-hour drive. While California’s coastal redwoods may be older–and the cool climate more pleasant to the perspiring hiker–nothing makes you realize your insignificance like standing next to a tree that is 20 feet around and 100 feet tall. How long had these trees been here? How many silent-footed inhabitants had they witnessed, before the settlers came?

As we worked our way along the loop to the trailhead, something happened that accelerated the last portion of our hike: quite unexpectedly, my husband’s cell phone rang, followed by a call on my cell phone. Since we were out of the service  area, the calls were lost almost immediately, but the number was not a familiar one. At the time, our three middle children were on an inner-city missions trip in another state. Little wonder that we both thought the worst and increased our pace for the last leg of the hike. While I retain a few memories of the enormous trees, of the amazing straightness of the tulip poplar trunks, of the leafy greenness of the woodland, what I mostly remember is intense anxiety as we rushed through the forest that we had invested so much time in coming to see. I did take a few photos of the memorial plaque as we passed it on the return trip; there were also two trees whose curiously intertwined roots had taken David’s fancy, so I spared a few seconds to photograph them.

area, the calls were lost almost immediately, but the number was not a familiar one. At the time, our three middle children were on an inner-city missions trip in another state. Little wonder that we both thought the worst and increased our pace for the last leg of the hike. While I retain a few memories of the enormous trees, of the amazing straightness of the tulip poplar trunks, of the leafy greenness of the woodland, what I mostly remember is intense anxiety as we rushed through the forest that we had invested so much time in coming to see. I did take a few photos of the memorial plaque as we passed it on the return trip; there were also two trees whose curiously intertwined roots had taken David’s fancy, so I spared a few seconds to photograph them.

But our enjoyment of the outing had ended with the ill-timed phone calls and their reminder that life was relentlessly being lived outside the boundaries of the forest. As it turned out, neither my husband nor I had cell service until we had driven well out of the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, my husband pointing out the road signs in both Cherokee and English as we drove. Eventually, we were able to listen to our voicemails. Predictably, the calls had nothing to do with our children. I still am not sure whether or not we should have had our phones on silent: what if there had been an emergency? Yet our hike was–if not ruined, at least made hostage to the pressingcares of this world.

One day, I hope to return to the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest–without a cell phone, with a water bottle, and with enough time to stop and go rafting in the cool, wild waters of the Nantahala River on the way home.